Study shows how mitochondria can shield cancer cells from chemotherapy

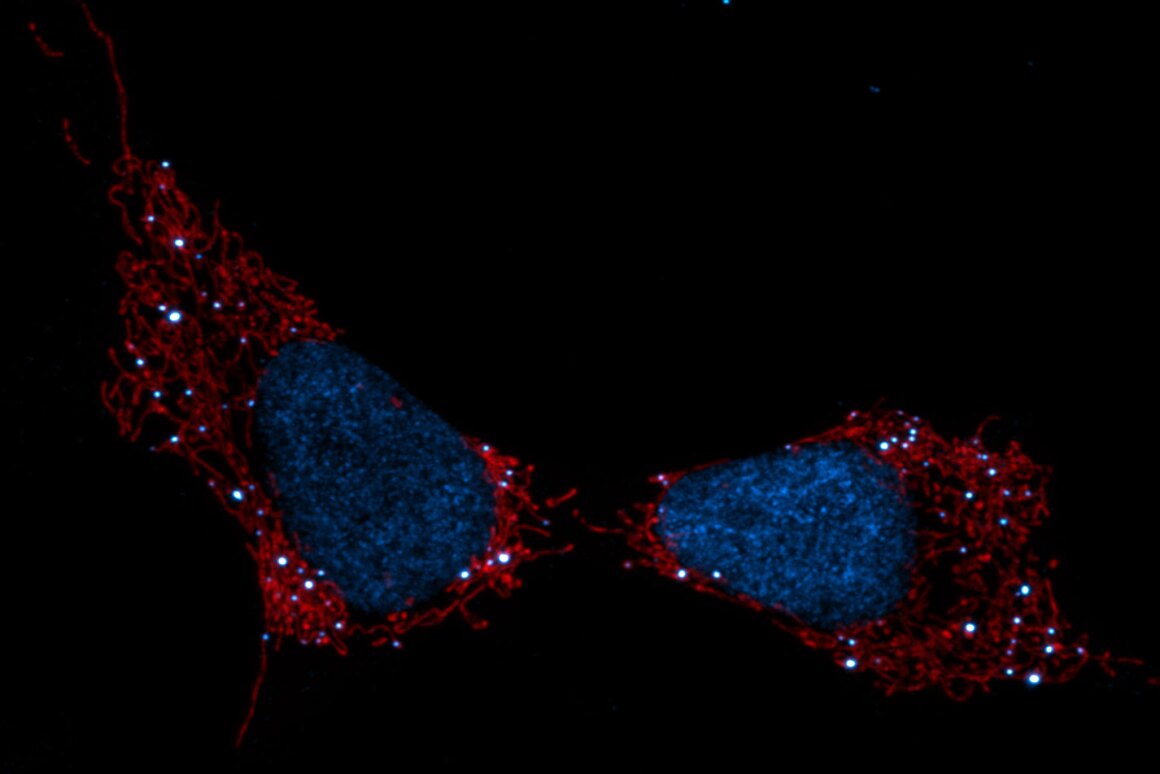

Mitochondria seen in red, cell nuclei (blue) and mtDNA (white dots)

Salk Institute/Waitt Advanced Biophotonics Center

VIEW 1 IMAGES

Chemotherapy is a powerful weapon in the fight against cancer, but the complex nature of the disease means that it doesn’t always produce the desired result. Scientists at the Salk Institute have been researching some of the cellular processes behind these evasive abilities, uncovering a new mechanism that could pave the way for new treatments that see chemotherapy maintain the upper hand.

The work was carried out at the Salk Institute’s Molecular and Cell Biology Laboratory, where medical scientists led by Gerry Shadel set out to investigate the role mitochondria might play in the effectiveness of chemotherapy.

Mitochondria is best known as the power generator of the vast majority of cells, but the scientists have found that it can also act as an early warning sign when something’s not quite right. While most of the DNA we carry is packed inside the nucleus of the cell, mitochondria packs its own small set of DNA, called mtDNA.

When our cells become stressed or are under attack by viruses or chemicals, such as those in chemotherapy drugs, the mitochondria responds by releasing its mtDNA and instigating an immune response to get on top of the threat. When this happens, a set of genes called interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs) spring into action.

These ISGs perform the role of shielding the DNA inside the cell’s nucleus. Unfortunately, it plays the same protective role when it comes to chemotherapy drugs that target the DNA inside cancer cells. The team observed this process at play in melanoma cancer cells grown in culture, and again in mice, where higher levels of ISGs led to higher resistance to chemotherapy drug doxyrubicin.

In this way, the mitochondria acts as a “canary in a coal mine” according to the researchers, serving as an early warning that the cells are under attack. But when this release of mtDNA is triggered by doxyrubicin, it has the undesired effect of protecting the nuclear DNA the drug is designed to attack. With this new understanding, however, comes potential new ways to intervene.

“It says to me that if you can prevent damage to mitochondrial DNA or its release during cancer treatment, you might prevent this form of chemotherapy resistance,” Shadel says.

Shadel and his colleagues are now working towards follow up studies to better understand these processes. The research has been published in the journal Nature Metabolism.

Source: Salk Institute