Treatment saved ~90% of terminal cancer patients, but it has scary side effects

Scientists cautiously optimistic about reprogramming immune cells to wipe out cancer.

WASHINGTON—Militarizing the body’s natural immune responses so that it can fight off cancerous uprisings has been seen as a promising strategy for years. Now, a sneak peek of data from a small clinical trial suggests that the method may in fact be as useful as doctors hope—but there are still some serious kinks to work out.

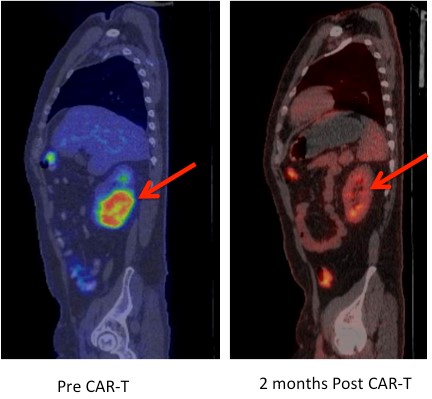

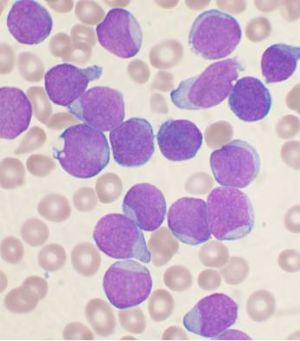

In a trial of 29 people with a deadly form of leukemia—acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL)—and no other treatment options, 27 went into remission after scientists plucked some of their immune cells, engineering them to fight cancer, then replaced them. The method was also successful at treating handfuls of patients with Non-Hodgkin lymphoma and chronic lymphocytic leukemia. The preliminary, unpublished findings were reported at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science in Washington.

While the early result suggests the treatment can be effective for these types of cancer, there were severe problems during the trials: several patients suffered extreme, full-body inflammation (cytokine release syndrome) in response to the treatment and needed to be placed in intensive care. Two patients died.

The risks may seem acceptable to terminal cancer patients who have exhausted all other treatment options and are facing a prognosis of just months to live. However, the severe reactions set the treatment option apart from standard cancer therapies, which are effective for many leukemia patients and have less dangerous side effects. It’s also unclear if the therapy would be widely effective against other types of cancer that have solid tumors, such as breast cancer.

It’s a “highly effective” strategy, said Stanley Riddell of the Fred Hutchison Cancer Research Center in Seattle, who presented the trial data at the meeting. But, he cautioned, there are challenges ahead to make the treatment safer and useful for other cancers.

In general, the treatment works by first collecting a patient’s immune cells—specifically T cells that patrol the body, seeking and destroying invading germs or foreign enemies. To do this, the cells look for certain molecular patterns found on those cellular combatants. But, once in lab, researchers can reprogram the T cells’ pattern recognition (antigen receptors) so that the cells target cancer cells. In this case, the resulting T cells, called CAR-T cells for “chimeric antigen receptors,” identify a protein called CD19, which is found on cells involved with lymphomas and leukemias.

This isn’t the first time such cells have been used in humans. Late last year, researchers in London announced they had engineered CAR T cells to save the life of a toddler with ALL.

Researchers are now working on ways to tweak the T cells and the treatment strategy to make safe, long-lasting cancer cures, researchers at the meeting reported.

No comments:

Post a Comment